We are familiar with the Koh-i-Noor diamond coming to the possession of the British Crown under the Last Treaty of Lahore (29th March 1849) after the fall of the Kingdom of Punjab. But we may not have read much about the events that led to the fall of the powerful Sikh Empire. The famous writer and Padma Vibhushan awardee Mr Khushwant Singh in his book titled “The Fall of the Kingdom of the Punjab” addresses this gap by taking us on a whirlwind tour of the turbulent period in India’s history preceding the East India Company’s usurpation of the Kingdom.

The book starts with the events following the death of Maharaj Ranjit Singh on the 27th of June 1839. In his time as the Maharaja for nearly four decades, he had led many expeditions and formed the powerful Sikh Empire that ruled over large portions of the (present-day) India Punjab, Pakistan Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir up to China. In the 180 pages of this compact book, the author narrates the quick succession to the throne by the many members of the royal family, who died untimely or murdered or were betrayed by the others and the aristocracy of the empire. The true story feels more cliché than a television soap opera. It was unbelievable to read on every page the brave sacrifices of the Khalsa (initiated Sikhs) army, in contrast to the selfishness of their rulers and the ministers. Reading about the many wives of the successive Kings and ministers committing the Sati by getting into the funeral pyre of their dead husbands, was horrifying to me.

The book was a by-product of the author’s research for three years exclusive of Sikh history, maybe because of this, the prose feels encyclopaedic and resembles less to the fluent language in his works of fiction. The book assumes a bit of knowledge of terms that will be familiar to Punjabis, but not to a South Indian reader like me. I had difficulty in following the various clans (Sandhawalias, Attariwala, Dogras) mentioned, understanding the Hindi (and Punjabi) words like Jagir, Jagirdas, Panches & so on, figuring who are Sardars & how are they different from Sikhs, and the various religious/military practises of the Sikhs. As a result, I had to refer to Wikipedia for many of the terms and then reread the paragraphs. Surprisingly for a publication by Orient Longman and now by Penguin Books, I was able to encounter quite a few typos on important dates mentioned, the names of people and places were spelt inconsistently throughout the book. Still, the book was fascinating for its subject matter and a must-read for those interested in an important chapter of the sub-continent history.

Now, let us see a summary of the decade of the decline of the Sikh Empire that gets covered in the book [I have quoted the dates from the book and those missing from Wikipedia].

Ranjit Singh (1801-1839)

During his rule, Ranjit Singh remained on friendly terms with the British but was fully aware of the threat from the East India Company to his empire. From 1822 to handle the eventuality he had been modernizing his army and inducting a stream of European (French, Italian, Greek, Spanish, English) and Eurasian Officers to his service. “When Ranjit Singh died on the evening of 27th June 1839, there was no one fit to step into his shoes and guide the destinies of the state. This applied not only to his (seven) sons but also to the rest of the favourites at Court whom he had raised from rustic obscurity to power, from modest means to wealth beyond their imagination”.

Kharak Singh (June 1839 – October 1839)

There were three major claimants to the throne, Ranjit Singh’s eldest son Kharak Singh, second son Sher Singh and Kharak’s son Nao Nihal Singh. Kharak Singh was described by the royal physician Dr Martin Honingberger to be “a block-head, he was a worse opium-eater than his father”.

Two factions of nobility at court arose during the power vacuum. One was the three Dogra Brothers: Gulab Singh (who later founded the Dogra dynasty and became the Maharaja of the Princely state of Jammu and Kashmir), Dhyan Singh, Suchet Singh and Dhyan Singh’s son Hira Singh. The other faction opposed to the former were from three families related to the Royal family: the Sandhawalias, Attariwalas and Majithias. After much wrangling and assurances were given, Kharak Singh came to the throne as the Maharaja and Dhyan Singh Dogra as the chief minister. The Maharaja was seen to be under the influence of one Chet Singh Bajwa, the manager of his personal estates.

Nao Nihal Singh (October 1839 – November 1840)

Shortly (8th Oct 1839) Chet Singh was murdered by Dhyan Singh who was loyal to prince Nao Nihal. Nao Nihal Singh, though only 18 years old was ambitious, pleasant and had led war campaigns on behalf of the Durbar. With the killing of his advisor, Kharak Singh got demoted to be only a figurative head of state, and the real power slipped smoothly to the young prince’s hands.

After a year, on 5th November 1840, due to drug overdose Maharaja Kharak Singh died, “two of his widows and eleven maid-servants mounted the pyre. The widows put the saffron mark on the foreheads of the new Maharajah and the chief minister”. The party from the funeral was passing through the Gate of Splendour (Roshini Durwaza) when the arch of the gate gave away and fell on the head of Nao Nihal Singh and soon, he died, on the same day as his father. On 11th November 1840, two of his consorts mounted the pyre with him. The same act like last time repeated with the Satis applying saffron on the foreheads of Sher Singh and the chief minister, the same Dhyan Singh.

Chand Kaur (November 1840 – January 1841)

Unfortunately, Chand Kaur (widow of Kharak Singh and mother of Nao Nihal Singh) and the noble families in support of her resisted Ranjit Singh’s second son Sher Singh’s ascent to the throne. Instead, Chand Kaur was formally installed as the Queen Empress, with Sher Singh (unwillingly) becoming the President of the Council of Ministers. Dhyan Singh was dismissed from being the Chief Minister. The English too recognized the Mai’s (as Chand Kaur was called by the people) government.

Sher Singh (January 1841 – September 1843)

Then on 18th January 1841, Sher Singh did a coup and seized the Lahore fort, to become the new Maharajah of Punjab. Gulab Singh Dogra (who later became the Maharaja of Kashmir) who was supporting Chand Kaur, as a token of surrender handed over the Koh-i-Noor diamond (the Durbar had appointed him as the custodian for the diamond) to Sher Singh.

In a sign of reconciliation between the rival factions, Chand Kaur, the widow of Kharak Singh, got engaged to marry the new Maharaja (Sher Singh), and, Dhyan Singh became the Chief Minister again. Soon, Chand Kaur was found murdered in her apartment – no one knows who ordered the murder, but it could be either Dhyan Singh or his elder brother Gulab Singh who were supporting different factions who were competing for the throne.

After consolidating his power, Sher Singh authorised one Zorawar Singh, who had taken over Ladakh in 1834 for the Durbar, now to proceed towards Tibet where he hoisted Durbar’s flag at Tuklakote on 29th August 1841. But the Chinese waited for few months and annihilated the Punjabi’s during the cold winter. Though the Tibetan adventure rattled the friendship of the British and the Durbar, the British had to give up their protest and co-operate due to the uprising in Afghanistan. A Punjabi-British venture to put Shah Shuja on the throne in Kabul failed and Amir Dost Mohammed was brought back to Kabul.

These led the Anglophone Sher Singh to start taking the threat from the British to his throne seriously, he even entered into a separate agreement with Dost Mohammed, recognising him as the Amir of Afghanistan. The British sensing their cooling relationship, brokered with the Durbar to have Sher Singh give amnesty to the estranged players, the Sandhawalia Sardars Ajit Singh and Attar Singh. Then, on the 15th September 1843, the Maharaja was given a salute at a march past of the Sandhawalias troops, when Ajit Singh shot and hacked Sher Singh’s head and mounting it on his spear. Soon, Lehna Singh Sandhawalia severed the head of Sher Singh’s child Pertap Singh. Then Ajit Singh shot Chief Minister Dhyan Singh in the back to revenge for the killing of his sister-in-law Chand Kaur, Dhyan Singh’s limbs were dismembered and thrown in the gutter.

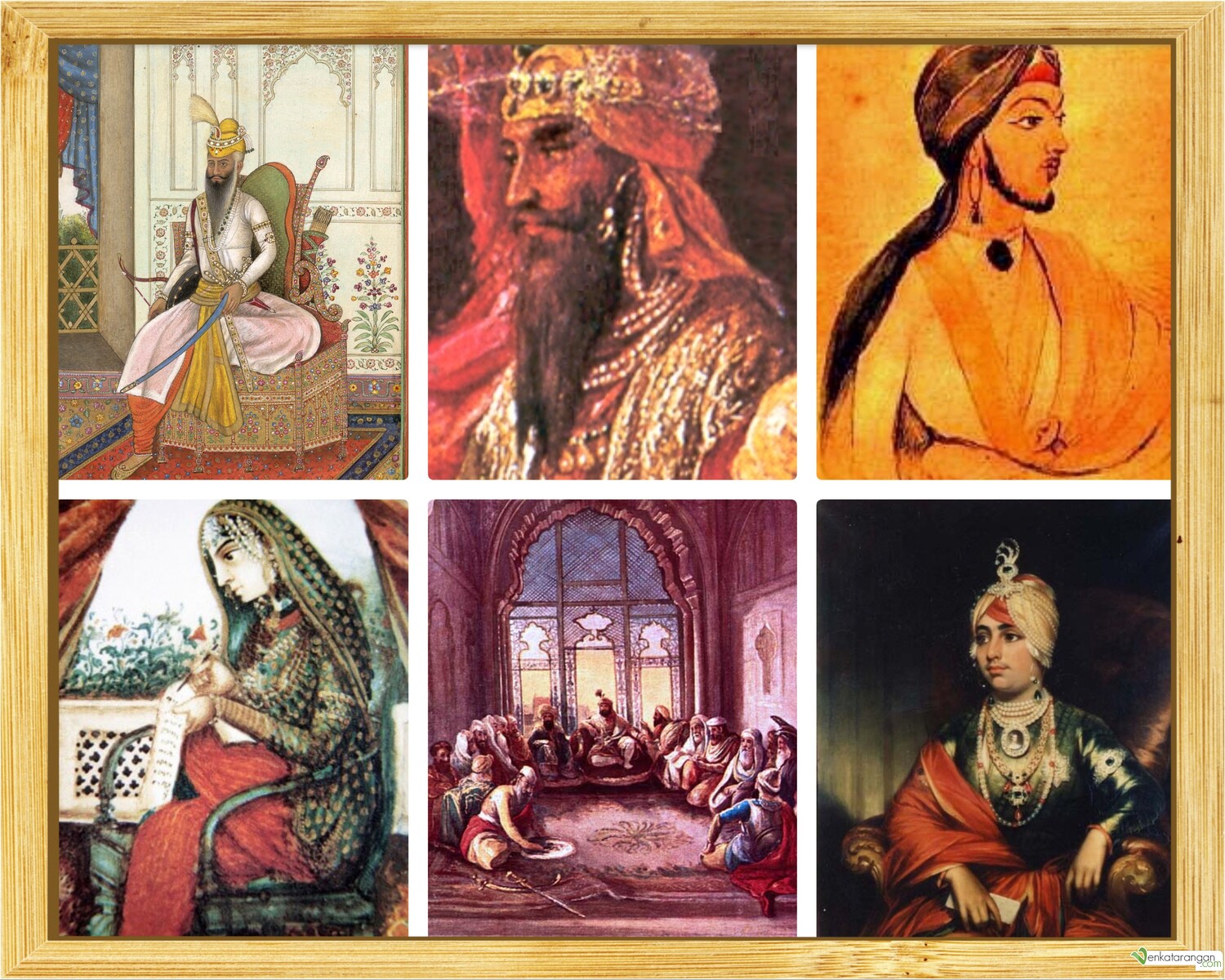

(Left to right top row & then the bottom row) Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Kharak Singh, Nau Nihal Singh, Chand Kaur, Sher Singh & Duleep Singh. Images courtesy: Wikipedia

Dalip Singh aka Duleep Singh (September 1843 – March 1849)

Hari Singh as the Chief minister

Dhyan Singh’s son Hira Singh promised revenge on the Sandhawalias, and the next day (16th September) he murdered two of the killers Ajit Singh and Lehna Singh, the third Attar Singh fled across the Sutlej and got refuge with the British. In the funeral for Dhyan Singh, his widows and maid-servants took their places in the pyre. This made Hira Singh powerful in the Durbar however since he was not from Ranjit Singh’s family he couldn’t claim the throne, so he became the Chief Minister (the same post his father served for long) and named the youngest son of Ranjit Singh, the five-year-old Dalip Singh as the Maharaja with Dalip’s mother Maharani Jindan as the Regent. Hari Singh Dogra’s uncle Suchet Singh was rumoured to be the lover of the widow, Maharani Jindan and he might’ve convinced Hari Singh on this.

Hari Singh now could clearly see the English turning hostile towards the Durbar, so he moved his troops to Kasur, which was facing the English’s fort of Ferozepur. At the same Suchet Singh conspired against Hari Singh and got killed in an encounter with the Durbar troops. But instead of Hari Singh getting the estates of his uncle (Suchet Singh), Gulab Singh assumed all of them, as his son Ranbir Singh had been adopted by Suchet. By now, it was reported that the British were massing a large army in the Simla Hills to invade Punjab. Also, by now, Ranjit Singh’s remaining two sons (with the youngest Dalip being the Maharaja now) Peshaura Singh and Kashmira Singh joined hands with Attar Singh Sandhawalia. Following this, the peace-initiative that was brokered by a respected Bhai Bir Singh between them and the Durbar turned bloody – Attar Singh provoked the Durbar troops who then killed him, and the Prince Kashmira Singh & Bhai Bir Singh. Later the Durbar troops went to Jammu and Gulab Singh submitted without a fight and made peace with his nephew Hari Singh, the Chief Minister.

Jawahar Singh as the Chief Minister

Hari Singh’s advisor Pandit Jalla accused the widow Maharani Jindan to be pregnant with a child of Lal Singh. This caused the Durbar troops to revolt against their Chief Minister, as a result, Hari Singh and Sohan Singh (the other son of Gulab Singh) were killed on 21st December 1844. Jindan’s brother Jawahar Singh became the Chief Minister. [The advisor to Hari Singh, Pandit Jalla owned a plot of open land in the heart of Amritsar, which became infamous 75-years later – it was the Jallianwala Bagh]

By now, in 1844, the English had prepared a blueprint for their invasion of Punjab. Sir Henry Hardinge as Governor-General of India appointed Broadfoot as the British Agent at Ludhiana, who proclaimed the territories of Punjab, on the eastern bank of the Sutlej to be theirs on the principle of extinction of the line of succession, when Maharaja Dalip Singh was in a sickbed. To instigate further, Broadfoot fired at a party of Durbar who had crossed Sutlej into their own territory, this unprovoked and unwarranted attack was said to the ‘first shot of the Great Sikh War’. Later, a conflict happened again between the Durbar troops and Gulab Singh, who had surrendered and heavily fined by Jawahar Singh. This made Gulab Singh determined to teach the Durbar a lesson, even if it involved dealing with the English. The English were making their own moves too, they used their pawn, the Prince Peshaura Singh (the only other son of Ranjit Singh other than the present Maharaja) who had returned to Lahore. Peshaura Singh headed a small revolt against the Durbar, but the army (Panches) resisted it and killed the Prince. Soon, the army realised they have been tricked by the warring Royal families and started to take things on their own hands under the banner of Khalsa Panth – they ordered Chief Minister Jawahar Singh, the Regent Maharani Jindan and Maharaja Dalip Sing to appear before an army tribunal and explain the death of Prince Peshaura Singh. Not able to do anything else, the trio appeared, when Jawahar Singh was killed, and the Maharani humiliated by having her elephant kneel down on the 27th September 1844.

Lal Singh as the Chief minister

The growing threat from the East (British India) made the council of ministers trusted by the army to bring the Kingdom together, and the Khalsa Panth leaders took an oath of allegiance to Dalip Singh and Jindan. Lal Singh was appointed as Chief Minister and Tej Singh as Commander-in-Chief. The Durbar army crossed the Sutlej on 14th December 1845, which led to Lord Hardinge declare war against Punjab. But many connected with Anglo-Punjab politics of the day didn’t find the move by Durbar to have been in violation of the treaty between the English and the Punjabis.

Then a few wars were fought between the two on Mudki and Ferozeshahr on December 1845. Though fighting bravely and better, the Punjabi army lost the war due to their leaders Lal Singh and Tej Singh conspiring with the enemy. Similar results happened on January 1846 at Buddowal & Aliwal. Then the next month at Sabraon nearly 10,000 Punjabis were killed. Lord Gough described Sabraon as the Waterloo of India.

The treaty of Lahore

Soon, Gulab Singh brokered a surrender of the Durbar to the British, who were receptive to him as he had kept aloof from the military campaigns against them and he was assured by Major Lawrence that his interests would be considered. Lord Hardinge though wanting to annex Punjab outright, realised it cannot be done now as the Durbar still had a larger army than the English and the Hindustani sepoys fought poorly against the Punjabis. Instead, he decided to annex in two stages, taking half each time. On the 8th March 1846, the Treaty of Lahore was signed. A British force was kept for the protection of the Maharajah at a payment of 22,000 Pounds, a council of Regency was set up to administer the state, Rani Jindan continued as Regent, Lal Singh as her Chief Advisor and Major Henry Lawrence was posted at Lahore as Agent of the Governor-General.

Kashmir sold to Gulab Singh, Maharajah of Kashmir

As part of The Treaty of Lahore, Kashmir was sold to Gulab Singh Dohra who was given the formal title as the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir. Soon a small revolt happened against Gulab Singh by Kashmir’s Governor Shaik Imamuddin, Lawrence took the Durbar troops and defeated them. A British court found Lal Singh to be guilty of working with the Kashmir Governor and exiled him out of Punjab – Lal Singh lived in obscurity from then till his death in 1867.

The Second treaty of Lahore & British Resident

Soon Lord Hardinge took the next steps to consolidate their hold. The Second treaty of Lahore was signed on 16th December 1846 with a new council of ministers formed which included Tej Singh and Sher Singh Attariwala (whose sister was engaged to the Maharajah). A British Resident took the maintenance of administration and the protection of the young Maharajah. Also, Rani Jindan was deprived of all her powers and was sanctioned a pension of Rs 1.5 Lakhs per annum. As she resisted the British influence, her allowance was reduced to Rs 48,000 per year and she was put under house arrest. This outraged the sentiments of the people, and soon a populace rebellion against the British was created under the leadership of an unlikely person Mulraj, son of the earlier administrator of the district of Multan. Initially, Chuttar Singh and his son Sher Singh Attariwala sided with the British Resident, but soon realised the true intention of the British.

Lord Dalhousie & the end of the Kingdom

Now, Lord Dalhousie had come as the new Governor-General of India. He decided to fight a war, but against whom was the question? Maharajah Dilip Singh and the majority of the council of Regency had not revolted. The rebellion was led by Mulraj and Attariwalas who were both fighting against the British. On the 13th January 1849, Sher Singh Attariwala scored a victory against Lord Gough’s troops at Chillianwala with over 3,000 British dead or wounded. The British soldiers who were captured as prisoners complimented on how kindly they were treated by the men of Sher Singh and were showered with gifts.

But in the war at Gujerat on the 21st February 1849, fate reversed and the British won, thanks to the help of the arch-traitor Gulab Singh Dogra who cut off Sher Singh’s retreat and arranged boats for the British army to cross the Jhelum. The Attariwala Sardars (father Chettar Singh and the son Sher Singh) surrendered to the British and on the 29th March 1849, Lord Dalhousie’s Secretary Mr Eliot called a durbar in the fort and declared the end of the Kingdom of Punjab. Maharajah Dalip Singh handed over the Koh-i-Noor diamond and stepped down from the throne at the age of Ten.

Dalip Singh in Europe (1854-1887)

Dalip Singh was exiled to Uttar Pradesh, where he converted to Christianity and went to England, with a copy of the Bible presented to him as a parting gift by Lord Dalhousie. In England, he was treated by Queen Victoria as her godson and was given a rich allowance and a large estate in Suffolk. Soon his mother Jindan also came to stay with him. When she died, he came to India with her ashes and en route to his return to England, he met an Abyssian woman Bamba Muller and married her in Alexandria. The two lived for the next two decades in Suffolk and raised six children. Later, getting tired of the British’ social life and disillusioned Dalip Singh toyed with the idea of returning to India and reclaiming his kingdom, but no one took him seriously.

Mr Kushwant Singh ends the book with these lines: “In the Great Mutiny of 1857, only eight years after the annexation of their kingdom, the Punjabis helped their erstwhile conquerors to defeat their Hindustani compatriots. … Many were proud to be the foremost in loyalty to the British Crown, … they were pleased to be known as ‘The Sword arm of the British Empire’ ”.

Comments