With the dominance of Apple and Google on the mobile phone market in the last decade, I feel puzzled and sorry for the two earlier leaders in the space – BlackBerry and Nokia. Both were dominating mobile giants and not from the USA. BlackBerry was from Canada, a country I have travelled to briefly on a weekend trip to Vancouver from Seattle. Even today in tech circles I hear people talking with high regards for the technology chops of BB. As a result, I always wondered where the company stumbled and this book “BlackBerry Town” by Chuck Howitt will shed some light to it.

As I started reading the book (a review copy on request was shared to me by the author’s office) I quickly realised it is not exclusive to the rise and fall of a single company, the Research in Motion (RIM) aka BlackBerry. Before reading the book, I would’ve found it difficult to identify in a world map where was BlackBerry’s hometown Waterloo was – it is about 100 kilometres from Toronto. The book is a well-researched work about the fertile soil of the twin cities of Kitchener-Waterloo that has given birth to quite a few technology companies whose products we might have used without being aware of their origins. The reality-distortion (borrowing the term from Steve Jobs) of Silicon Valley outshines us blind to the happenings every else, especially to its northern neighbour.

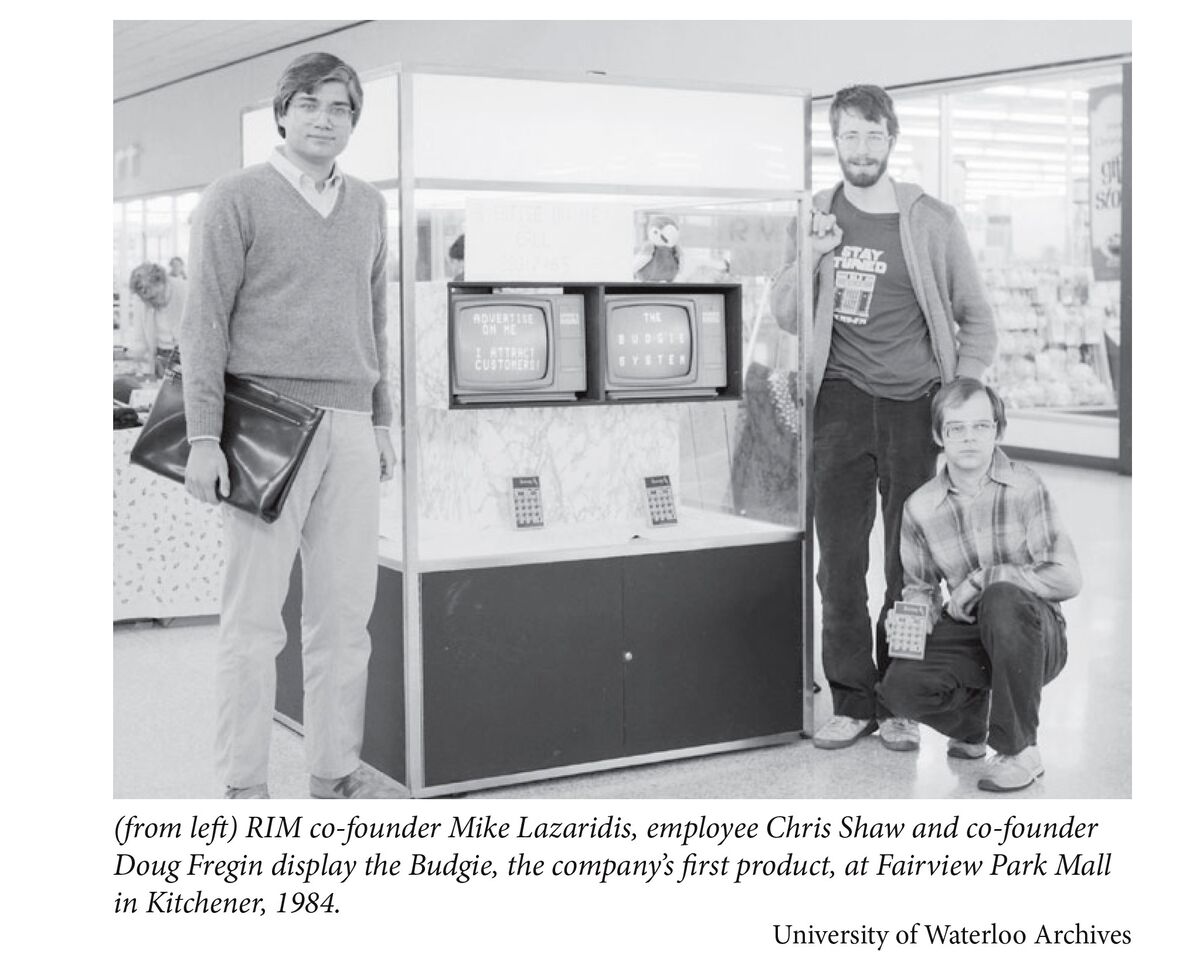

The book starts with the time Mike Lazaridis, the co-founder of Research in Motion was a student in the wireless communications class at the University of Waterloo (UW). Even as a student Lazaridis was well-informed about the latest inventions in the space and had keenness to keep learning, so it was no surprise he went on to run one of the iconic technology companies.

Howitt then takes us on a journey about 60 years ago to the founding of the University of Waterloo by its first President Gerald Hagey. He created an engineering program that was well-rounded with students getting an opportunity to learn from literature, history, politics and humanities. The university with its Cooperative education (combining classroom-based education with practical work experience) would prove to be disruptive. Today, UW operates the largest post-secondary co-op program of its kind in the world, with an enrolment of 19,800 students and 6,700 employers. And its computer science department under James Wesley Graham would become famous with many Silicon-Valley employers. Graham had created innovative high school math contests to attract the brightest to the young university. He also created the Computer Systems Group, the equivalent to modern-day incubators. An earlier success from this was Watfor (Waterloo Fortran) compiler which led to the creation of one of the well-regarded compilers for C/C++, the Watcom. Another success was Open Text, the multi-billion-dollar tech giant, which germinated from a search engine build by the department for the Oxford English Dictionary. Another spinoff from UW was Maplesoft, the software for Mathematics.

RIM co-founder Mike Lazaridis, employee Chris Shaw and co-founder Doug Fregin display the Budgie, the company’s first product, at Fairview Park Mall in Kitchener, 1984.

The book returns back to BlackBerry. One of the first products they make was an electronic barcode reader for National Film Board of Canada for a new kind of film Kodak had developed, using the shiny new CPU from Intel. RIM earned over $1 million in 1990. Then in 1992, Lazaridis got Jim Balsillie onboard, where they both served as Co-CEO till 2012. The next breakthrough the company got was to send messages between a computer and a Mobitex radio for Rogers Cantel, a telco in Canada. Following this were deals to supply modems and point-of-sale terminals to leading manufacturers. Then came the first pocket device from RIM, the Inter@ctive Pager 900 around 1996. Here, it was interesting to see how the top brass got the top management at the tech giant Intel to give them chips when they didn’t want to do – Intel had wanted to cancel a handshake deal an Intel executive Gillet had made with RIM. After this came the 950 pagers, that can deliver email. Howitt writes about how for a crucial meeting with BellSouth in Atlanta, the Co-CEOs of RIM had come with a mock-up of 950 but had left it behind in a taxi they had taken from the airport; read the book to learn on what happened to the mock-up. The BlackBerry pagers in 1998 could receive message up to 2600 words in second and on a battery that lasted up to three weeks!

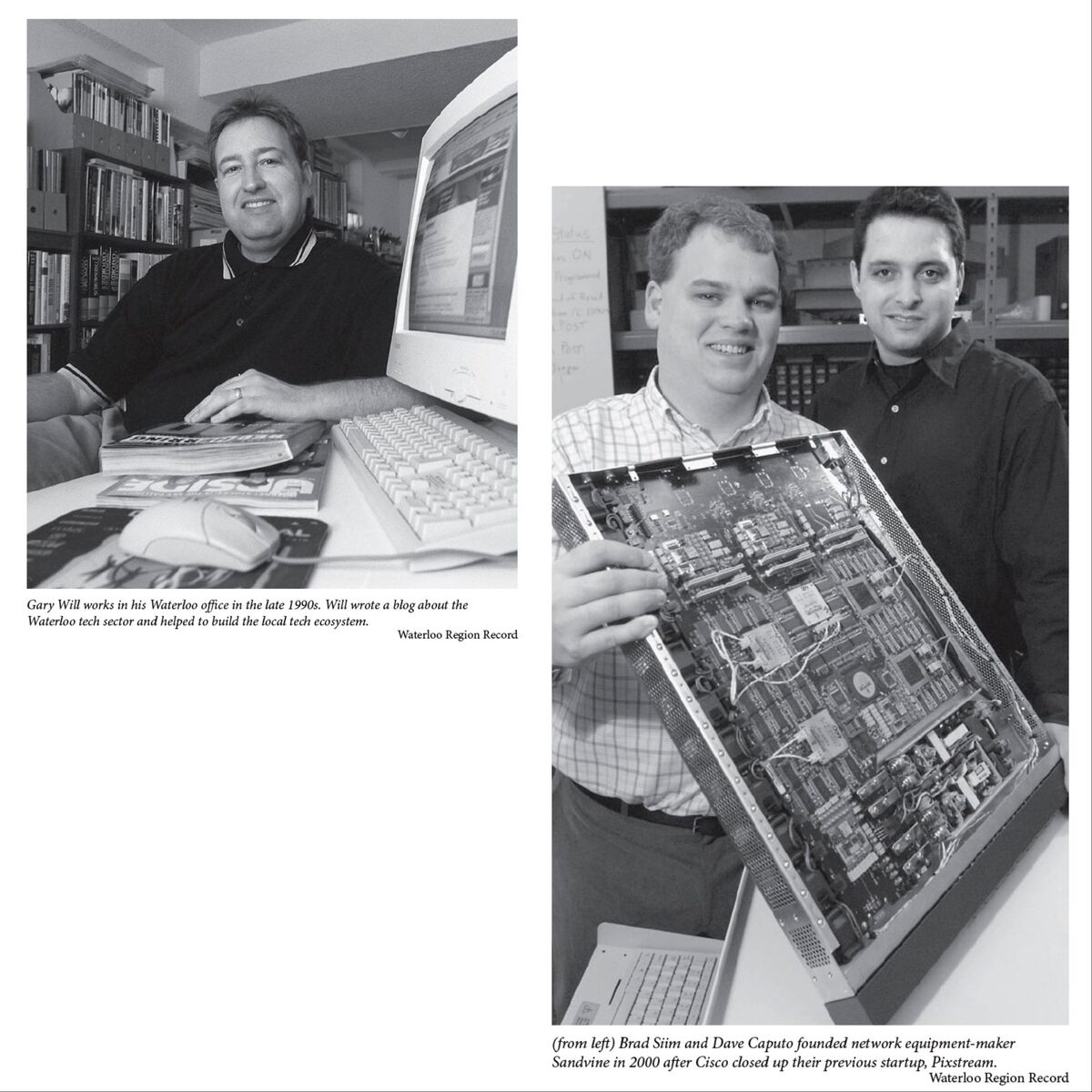

In 2000, RIM shares cracked the $100 barrier on the NASDAQ and the Co-CEOs of RIM became billionaires. Around the time there were only eight billionaires in all of Canada. Here the book starts talking of a local tech-consultant and blogger Gary Will; a real-estate veteran John Whitney and about local press reporters. In 1999, a young Pete Gould got a big break for RIM by getting the stockbrokers and lawyers in Wall Street to start using BlackBerrys. Lindsay Gibson, who worked in the marketing in the 2000s scored big for RIM by arranging to gift the latest BlackBerrys to Oprah audiences in the popular TV show. In the early 2000s, the real-estate scene in the Kitchener-Waterloo cities was overheating with RIM occupying ever more offices and many of the millionaire employees of the company buying houses worth over half-a-million dollars! This was also the time RIM was handing out stock options by the wheelbarrow to its over 2,000 employees, a practice of backdating here led to legal trouble for the company later.

Lazaridis and Balsillie poured hundreds of millions of dollars to set up Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics (a think tank), Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Balsillie School of International Affairs and The Institute of Quantum Computing at the University of Waterloo.

Apart from Open Text, a few other high-tech companies from the Waterloo region went public around 1997. One was MKS (Mortice Kern Systems) which made popular version control, software change management and other application lifecycle products. The second was Descartes Systems Group that made supply chain management and logistics software. The third was Com Dev that made components for space satellites. The fourth, an interesting one from the vantage of 2020, was Dalsa Corp that made an image sensor microchip that could capture tiny images in sharp and precise detail. Earlier to these, Waterloo had a large electronics manufacturer, a company called Electrohome which was making TVs before the arrival of Japanese on the scene. Electrohome merged with Christie in USA, they both were working on digital cinema projectors, after the merger the R&D and manufacturing was kept in Kitchener because Electrohome was further ahead in its research.

The book moves its attention to Open Text and its CEO Tom Jenkins. The company had one of the best search engines, which competed favourably with Excite from Stanford, Lycos from Carnegie-Mellon, Infoseek from University of Massachusetts, and Alta Vista from Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC). But in 1996 when Yahoo! signed a deal for free with Alta Vista, Jenkins decided to abandon the public search engine market to focus on Intranet – where it is still a market leader. The company’s origins came from the work of digitizing the 60 million words and 600,000 definitions, a task that would take the team three years and 400 million keystrokes. In 1996, Open Text made a merger with Odesta Systems, which made Livelink, allowing users to collaborate on documents from different locations.

Then comes the discussion about Pixsteam, a company that allowed telecoms to deliver phone, Internet and TV Channels over cable/phone lines. In 2000, Cisco acquired Pixstream for US$369 million. Over the decades, many startups came out of the former employees of Pixstream. Sandvine, a product for network management, was one, they are still around and successful.

Gary Will a tech blogger and Brad Siim and Dave Caputo of Sandvine

Communitech, an incubator that came up in the old Tannery in Waterloo had produced several other successful technology startups as well. Its early head was Iain Klugman. One of the early successes at Communitech was Desire2Learn. The internet giant Google too had set up an office there.

The Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics setup by generous donations from Mike Lazaridis of over $100 million, works on solving abstract problems in physics over decades, as mentioned in the book titled First Principles: The Crazy Business of Doing Serious Science by Howard Burton. The institute is unique as it is not affiliated with any university and it doesn’t own IPs, with papers posted on the archive as soon as they are written. Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) is a Waterloo-based research institute on global affairs founded by Jim Balsillie in 2001. CIGI in its early days focused on G20, which was founded in 1999 by then-Canadian finance minister Paul Martin and US treasury secretary Larry Summers, the G20 brought together finance ministers from nineteen leading nations and the European Union to discuss ways to improve global financial stability.

Around 2000 when RIM brought in people from outside at higher levels, from companies like Nortel Networks, the new people brought politics to the company which for a long time was flat. Layers were added in between the Co-CEOs and the others, messages were being massaged, mini-empires were being created. RIM had produced a lot of quality leaders like Patrick Spence who had joined RIM right out of Western University in London (Ontario) to rise through the ranks to become Senior VP of global sales in 2012, today he is the CEO of Sonos, the Home-Sound system with over billion dollars in revenue. Dietmar Wennemer, a mechanical engineer worked with the mobile phones division at Siemens, joined RIM in 2005 as director for mechanical engineering. He regards the act of Android allowing Asian manufacturers to get in the game really killed BlackBerry and not the iPhone. Mark Pecen, a veteran from Motorola where he had developed new technologies and protocols that went into the Global System for Mobile Telecommunication (GSM) standards, joined RIM in 2005; at one point he had over 300 researchers spread over four cities working for him. In 2015, Pecen joined ISARA Corporation who make crypto-agile and quantum-safe security solutions. Lindsay Gibson who was part of the sales and marketing team describes the BlackBerry UI to be not in touch with consumer needs.

One of the reasons for BlackBerry losing out to iPhone was the robust web browser that came in the latter, while RIM’s carrier partners prevented BlackBerry from having one itself for fear of overloading and crashing their wireless networks.

The Record newspaper’s Matt Walcoff reported extensively on the story of NTP Inc’s patent case against RIM around 2005 which led to a settlement of $612 million by RIM.

Dalsa, started in 1980 by UW professor Savvas Chamberlain had been making image sensors used in fax machines, cheque-scanning equipment, medical imaging for a long time. Its venture into digital cinema camera was by accident when it developed a sensor for use in an HDTV camera in Japan. Its cinema camera cost over $300K to 400K and took a long time to get market acceptance, but eventually, it did.

Christie Inc, which was selling digital projectors costing about $100K a device, one of the managers from Canada, Gerry Remers came up with a solution for the high price – Instead of Theatres paying for the digital projectors, Hollywood studios would pay a fee every time one of their films was screened on a new Christie projector, the fee coming from the money saved by the studios through digital’s lower distribution costs. When Remer had stepped down as President and COO the company had over 47,000 digital cinema projectors in movie theatres around the world.

Clearpath Robotics was started in 2009 to serve the education sector by offering robots to be used as prototypes in classrooms. Now the company has clients like Toyota, Caterpillar, General Electric and John Deere. Vidyard is a video-marketing startup, raised over US$50 million in 2016, whose founders Michael Litt and Devon Galloway were able to impress the Y-Combinator judges by the wealth of real-time data their system could provide. Another company from the twin-cities was Miovision, founded in 2005, the firm uses cameras mounted at intersections to monitor and analyze city traffic.

The book will be a treasure for the residents of the twin city of Kitchener-Waterloo and for Canadians, but for those who are not, it felt a bit too much to take in. There are many pages devoted to how the real estate business in the city skyrocketed and then crashed matching with the fortunes of Research in Motion and on how tech news reporting worked in the local newspapers. There were many biographies of lesser known (no disrespect to them) figures who had worked hard for the city’s tech ecosystem but these quickly starting to feel like reading Wikipedia entries. The non-linear narrative style made it difficult to mind map the various happenings that led to the rise and fall of BlackBerry as a company. In its coverage of RIM, the book leaves out a large number of years in between – I was curious to know what happened from their early years of success to the arrival of Android in the scene – but the book has little details on those years.

Thanks to Chuck Howitt’s BlackBerry Town, I got to learn a lot about the University of Waterloo and the ecosystem in the region.

Comments